-

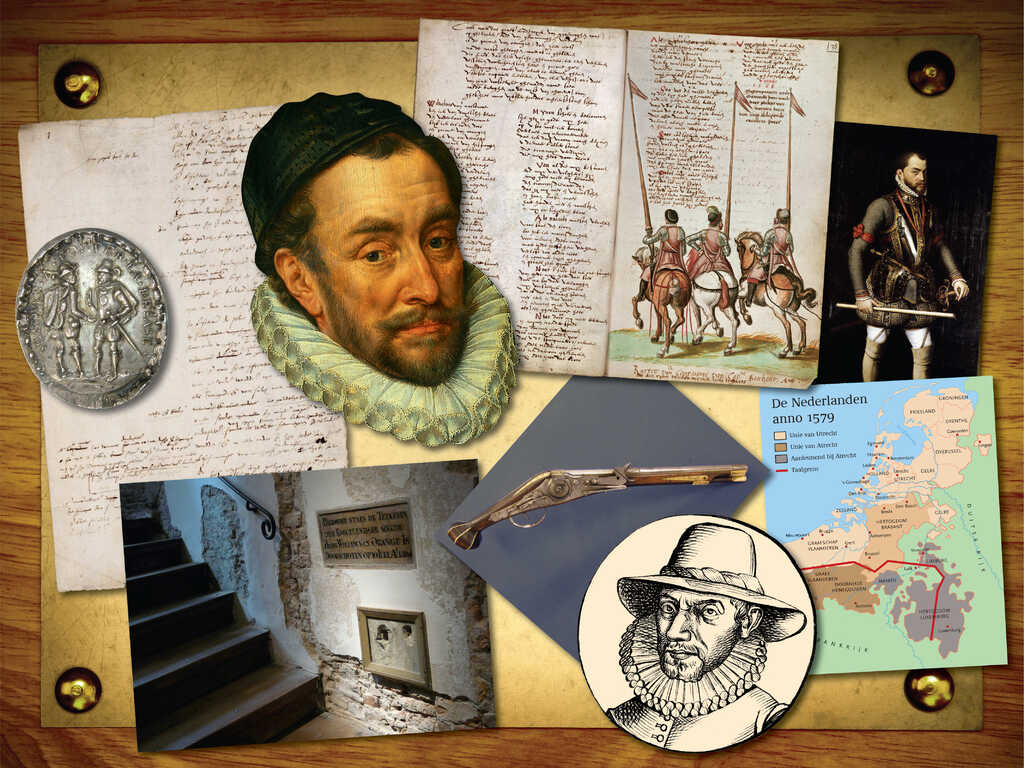

De moord op Willem van Oranje

Op 10 juli 1584 is er in Delft een moord gepleegd. Misschien wel

de belangrijkste moord van Nederland. Wij gaan die oude moord (dat

noem je een 'cold case') opnieuw onderzoeken. Het slachtoffer

heette Willem van Oranje. Wie was hij? En wie waren dader en

opdrachtgever? En welke bewijsstukken kun je vinden? Zoek je

mee?

-

Slachtoffer: Willem van Oranje

Willem van Oranje (1533-1584) wordt ook wel de 'Vader des

Vaderlands' genoemd. In de zestiende eeuw is hij een belangrijke

edelman en de leider van de opstand van de Nederlanden tegen

Spanje. Door deze gewapende strijd legt Willem de basis voor het

land Nederland zoals we het nu kennen.

Willem van Nassau wordt in 1533 geboren op een kasteel in

Duitsland. Hij is de oudste zoon van de graaf van Nassau. Van huis

uit spreekt Willem Duits en hij wordt opgevoed in het protestantse

geloof.

Als jongen van elf erft Willem van zijn neef het prinsdom Orange

(Frankrijk). Hij mag zich voortaan 'Prins van Oranje' noemen. Omdat

Willem nu een Franse edelman is geworden, moet hij van keizer Karel

de Vijfde naar Brussel komen. Daar krijgt hij een Franstalige en

katholieke opvoeding.

Karel de Vijfde is erg gesteld op de jonge prins. Hij maakt hem

opperbevelhebber van een leger. En als Karels zoon, Filips de

Tweede, zijn vader opvolgt, wordt Willem ridder en stadhouder van

Holland, Zeeland en Utrecht.

Willem van Oranje en Filips de Tweede kunnen het lange tijd goed

vinden met elkaar. Maar uiteindelijk zal deze vriend zijn grootste

vijand worden...

-

Opdrachtgever: Filips II

Dit is Filips de Tweede. Hij is niet alleen de koning van

Spanje, maar ook de baas over de Nederlanden. In 1580 zet Filips

een prijs op het hoofd van de leider van de opstandige Nederlanden:

Willem van Oranje. Wie Willem vermoordt, krijgt een grote beloning:

25.000 gouden munten. Ook zal hij in de adelstand worden

verheven.

Filips de Tweede volgt in 1555 zijn vader Karel de Vijfde op. Vanuit zijn paleis in Spanje regeert hij over zijn rijk. Dat rijk is heel groot. Daarom kan Filips nooit overal tegelijk zijn. Nederlandse edelen, zoals Willem van Oranje, besturen de Nederlanden in zijn naam.

Filips heeft grootse plannen met de Nederlanden. Er moet meer eenheid komen, vindt hij. Voortaan moeten overal dezelfde wetten en regels gaan gelden. Filips geeft Spaanse 'vrienden' de banen van de Nederlandse edelen. Hierdoor krijgen de Nederlandse edelen steeds minder te vertellen. Daar zijn ze natuurlijk boos over.

Ook wil Filips dat iedereen in zijn rijk rooms-katholiek blijft. Hij laat protestanten zwaar straffen en op de brandstapel gooien. De Nederlandse edelen vragen Filips tevergeefs een einde te maken aan deze geloofsvervolgingen.

De Nederlandse edelen en Filips krijgen steeds vaker ruzie met elkaar. Na de Beeldenstorm in 1566 barst de bom. Filips stuurt een groot leger naar de Nederlanden.

Willem van Oranje vlucht naar Duitsland. Daar bouwt hij een leger op. Onder leiding van hem vallen de Nederlanden de Spanjaarden aan. Het wordt het oorlog. Er wordt hard gevochten. Wel tachtig jaar lang!

-

Dader: Balthasar Gerards

Dit is Balthasar Gerards, de moordenaar van Willem van Oranje.

Deze Fransman is een strenge rooms-katholiek die niets van

protestanten moet hebben. Als hij hoort dat Filips de Tweede een

flinke beloning belooft aan degene die Willem vermoordt, wil hij

wel een poging wagen.

Op 10 juli 1584 loopt Balthasar Gerards rond half twee met twee

pistolen naar het Prinsenhof in Delft, het huis van Willem van

Oranje. Hij heeft eerder die dag een afspraak met Willem

gemaakt.

In de hal wacht Balthasar Gerards Willem op. Als de prins na de

lunch de eetzaal verlaat, schiet Balthasar hem van dichtbij in de

borst en in zijn zij. De prins zakt door zijn knieën. Volgens de

overlevering waren zijn laatste woorden: 'Mijn God, mijn God, heb

medelijden met mij en dit arme volk.' Willem van Oranje is

dood.

Na de moord vlucht Balthasar Gerards het Prinsenhof uit. Maar

hij wordt achtervolgd door soldaten en bedienden. Bij de stadsmuur

krijgen ze hem te pakken.

Ze verhoren Balthasar Gerards en hij wordt daarbij gemarteld.

Daarna wordt hij berecht.

De rechters besluiten dat Balthasar Gerards een verschrikkelijke

dood moet krijgen. Hij wordt gevierendeeld en onthoofd. Zijn

lichaamsdelen worden in de stad tentoongesteld, als afschrikwekkend

voorbeeld. Maar Willem kregen ze er niet mee terug...

Willem van Oranje wordt begraven in de Nieuwe Kerk in Delft.

Daar is zijn prachtige grafmonument nog altijd te vinden.

-

Moordwapen: radslotpistool

Wist je dat Willem van Oranje de eerste politieke leider was die

met een pistool is gedood? Balthasar Gerards gebruikte voor de

moord twee 'radslotpistolen'. Een radslotpistool past onder je

kleren, en je kunt het geladen met je meedragen. Een erg handig

wapen dus als je een beveiligd persoon in een onbewaakt moment wil

vermoorden.

-

Plaats delict: Prinsenhof, Delft

Willem van Oranje is vermoord in zijn eigen huis, het Prinsenhof

in Delft. De plek waar een moord is gepleegd noem je de 'plaats

delict'. Het Prinsenhof in Delft is nu een museum. Je kunt daar in

een muur nog altijd de kogelgaten van de moord op Willem van Oranje

zien zitten.

Een paar jaar geleden is opnieuw onderzoek gedaan naar de moord

op Willem van Oranje. Met schietproeven hebben ze de kogelgaten

onderzocht.

Voor het onderzoek is eenzelfde pistool gebruikt als waarmee

Willem vermoord is. De onderzoekers hebben de allernieuwste

technieken toegepast. Hierdoor konden ze precies uitzoeken waar

Willem van Oranje stond toen hij werd neergeschoten. En waar zijn

moordenaar, Batlhasar Gerards, zich bevond.

En wat blijkt uit het onderzoek? De kogelgaten in de muur zijn

groter en dieper dan de gaten die ontstonden tijdens het onderzoek.

Waarschijnlijk zijn de gaten in de loop der eeuwen steeds dieper

geworden omdat veel mensen eraan gevoeld hebben. Daarom zit er

tegenwoordig een glazen plaatje voor de gaten.

-

Bewijsstuk: kaart van de Nederlanden

Nederland zoals jij dat nu kent, bestaat nog niet in de

zestiende eeuw. Ons land wordt dan samen met België en Luxemburg,

'de Nederlanden' genoemd. De Nederlanden bestaan uit zeventien

kleine landjes (gewesten), met elk hun eigen wetten en regels. De

Spaanse koning Filips de Tweede wordt in 1555 de baas over deze

Nederlanden.

Steeds meer mensen in de Nederlanden zijn het niet eens met de

manier waarop Filips de Tweede bestuurt. Onder leiding van de

Nederlandse edelman Willem van Oranje komen ze in opstand.

Willem van Oranje wil drie dingen:

1) dat de Nederlandse edelen meer macht krijgen.

2) dat de Nederlandse edelen gaan samenwerken.

3) vrede tussen rooms-katholieken en protestanten.

Er breekt een oorlog uit die wel tachtig jaar zal gaan duren.

Later zijn we die oorlog de 'Tachtigjarige Oorlog' gaan noemen.

Na de moord op Willem in 1584 lijkt het even alsof hij niks

bereikt heeft. Maar nog geen vijfentwintig jaar later zijn de

opstandige Noordelijke Nederlanden (ongeveer het gebied dat we nu

Nederland noemen) samen één land. Willem van Oranje wordt sinds die

tijd 'Vader des Vaderlands' genoemd.

-

Bewijsstuk: geuzenpenning

Dit is een geuzenpenning. Deze is gemaakt in 1572. 'Geus' is een

bijnaam voor iemand die in de Tachtigjarige Oorlog tegen de

Spanjaarden vecht. Aan de kant van Willem van Oranje dus. Geus

betekent eigenlijk armoedzaaier of schooier. Maar de geuzen zijn

trots op hun naam! Ze dragen een geuzenpenning om hun nek, zodat

iedereen ze kan herkennen.

De groep geuzen die vanaf schepen vechten, worden 'watergeuzen'

genoemd. In 1572 veroveren de watergeuzen de plaats Den Briel (nu:

Brielle, bij Rotterdam) op de Spanjaarden. Ze hebben met Willem van

Oranje afgesproken dat zij de Spanjaarden vanaf zee zullen

aanvallen. Maar dan raken hun schepen onverwachts in een storm

verzeild. Ze komen per ongeluk terecht voor de haven van Den

Briel.

De watergeuzen horen dat de Spaanse soldaten op dat moment de

stad uit zijn. Den Briel wordt dus niet verdedigd! In naam van

Willem van Oranje nemen ze de stad in.

Den Briel is de eerste stad in de Nederlanden die zich officieel

bij Willem van Oranje aansluit. Hierna volgen al snel andere

steden. De opstand breidt zich nu in een rap tempo uit over de

Nederlanden.

-

Bewijsstuk: 'Plakkaat van Verlatinghe'

In 1581 schrijven een aantal Nederlandse gewesten het 'Plakkaat

van Verlatinghe'. Dat is een soort brief. In de brief schrijven ze

dat de Spaanse koning Filips de Tweede niet langer hun koning mag

zijn. Ze gaan op zoek naar een nieuwe koning. Je zou dus kunnen

zeggen dat het de onafhankelijkheidsverklaring van Nederland is.

Een heel belangrijk stukje papier!

De opstandige gewesten schrijven het 'Plakkaat van Verlatinghe'

nadat Filips de Tweede een prijs heeft gezet op het hoofd van hun

leider, Willem van Oranje. Ze voeren al een tijdje een gewapende

strijd tegen Filips de Tweede en nu is hij volgens hun echt

veel te ver gegaan.

In het 'Plakkaat van Verlatinghe' leggen de opstandige gewesten

uit dat het volk er niet is ten dienste van de koning, maar dat de

koning er juist is voor het volk. Hij is het verplicht om goed voor

zijn volk zorgen. Hij moet ze rust en veiligheid bieden.

Als een koning niet goed voor zijn volk zorgt, maar de mensen

angst aanjaagt, dan is hij geen koning maar een dwingeland en een

tiran. Zijn volk heeft dan het recht om de koning afzetten.

Wist je dat dit een erg moderne manier van denken is voor die

tijd? Bijna tweehonderd jaar later hebben de Amerikanen de ideeën

uit het 'Plakkaat van Verlatinghe' gebruikt voor hun eigen

onafhankelijkheidsverklaring.

-

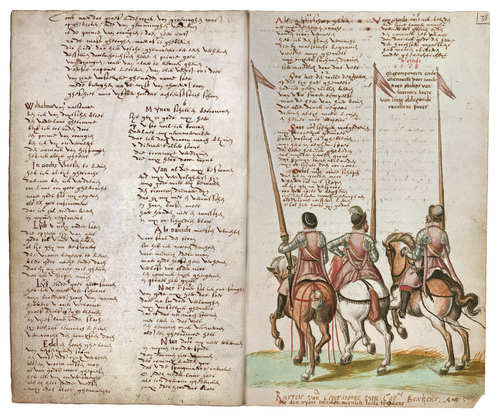

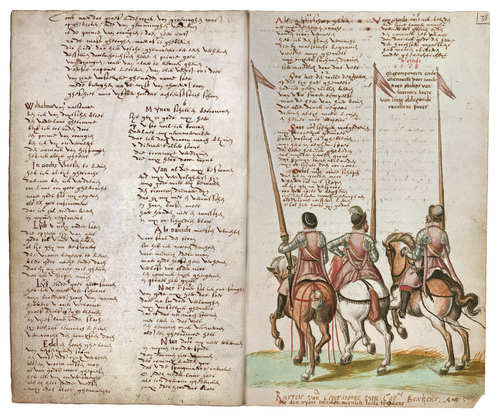

Bewijsstuk: het Wilhelmus

Willem van Oranje voert de strijd tegen Spanje niet alleen met

wapens. Hij vecht ook nog op een andere manier: via folders,

strijdliederen en spotprenten. Aan die strijd hebben we ons

volkslied, het Wilhelmus, te danken. Het lied gaat helemaal over

Willem van Oranje.

Het Wilhelmus is eigenlijk een gedicht dat gezongen werd.

Waarom? Als je tekst laat rijmen en op muziek zet, kun je het veel

beter onthouden. Erg handig als je een belangrijke boodschap wil

overbrengen in een tijd waarin de meeste mensen niet kunnen lezen

en schrijven!

We weten niet precies wie het Wilhelmus geschreven heeft. Vaak

wordt gedacht dat een vriend van Willem van Oranje, de edelman

Philips van Marnix van Sint-Aldegonde, de schrijver is. Maar dat is

niet helemaal zeker.

Wist je dat het Wilhelmus een heel lang gedicht is? Het bestaat

uit 15 coupletten. Als je van elk couplet de eerste letter

opschrijft, heb je de naam 'Willem van Nassau'.

Hoeveel coupletten van het Wilhelmus ken jij?