United Kingdom of the Netherlands

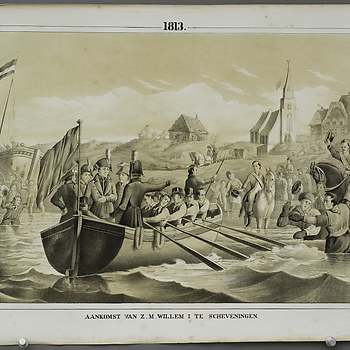

When Napoleon is defeated in 1813, the son of former Stadtholder William V is designated to assume the monarchy of the Netherlands. He accepts the crown and, after his exile in England, returns to the Netherlands. In 1814, he is inaugurated as King William I in the New Church in Amsterdam. This is a clear break from the past. William I does not become Stadtholder of all the provinces, like his father, but rather King of a unified state in which he plays a key political role.

In 1815, the former Southern Netherlands – present-day Belgium – are united with the territory of the old Republic. Thus, a United Kingdom of the Netherlands is formed: in European terms, a mid-sized country with colonial possessions in several continents.

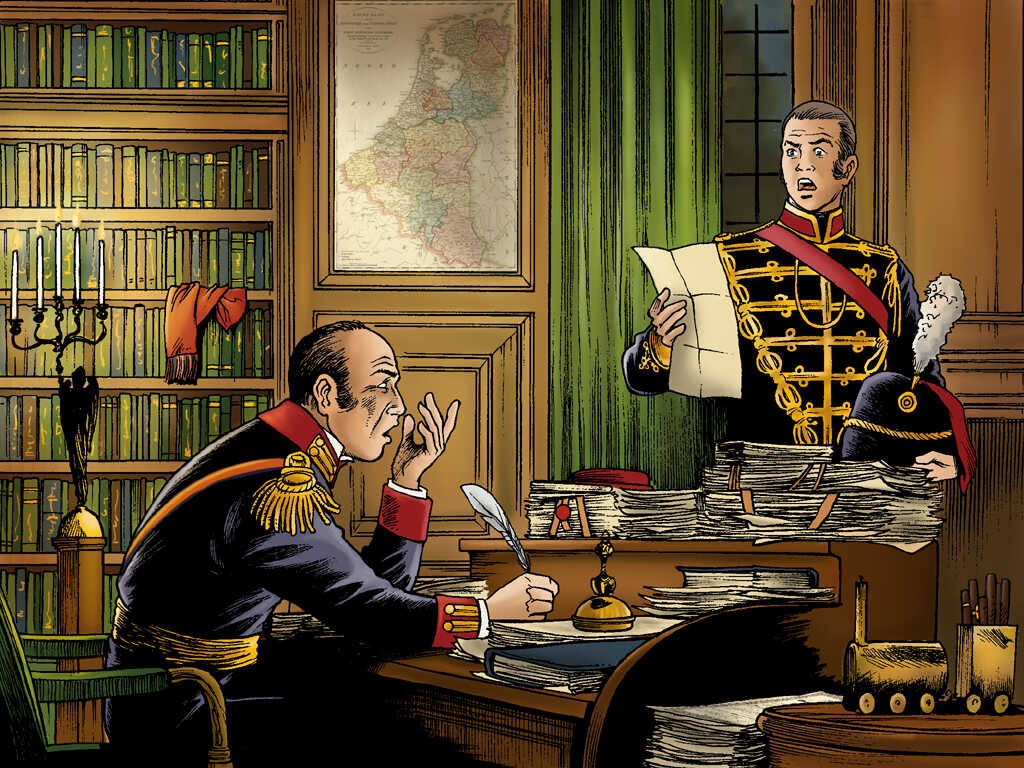

King-Merchant

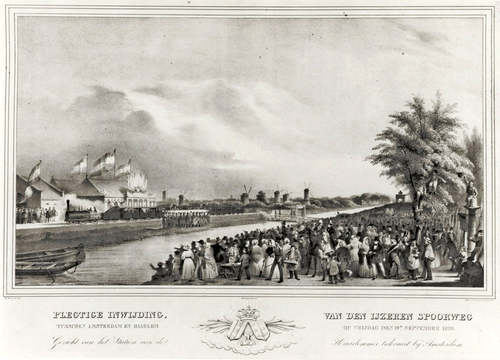

During his reign, the energetic William, dubbed “King-Merchant”, focuses on restoring the previously thriving economy. To this end, he boosts the economic strengths in the three parts of his Kingdom – the North, the South, and the colonial Dutch East Indies. The South – present-day Belgium – has already seen an industrial revolution and needs to focus on the production of consumer goods. Subsequently, it is up to the tradesmen from the North – now the Netherlands – to transport such products across the globe. The inhabitants of the colonies, finally, are to supply the valuable tropical goods. William I has canals and roads constructed between North and South to facilitate freight transport. These projects are co-funded from his own resources. In 1824, he establishes the Netherlands Trading Company in the purview of the trade with the Dutch East Indies. In this colony, he introduces the cultivation system, requiring the local population to work the fields for a certain period of each year, on behalf of the colonial authorities. Thus, the Dutch East Indies will help to set the economy of the fatherland back on its feet. The products are sold by the Netherlands Trading Company.

Belgian independence

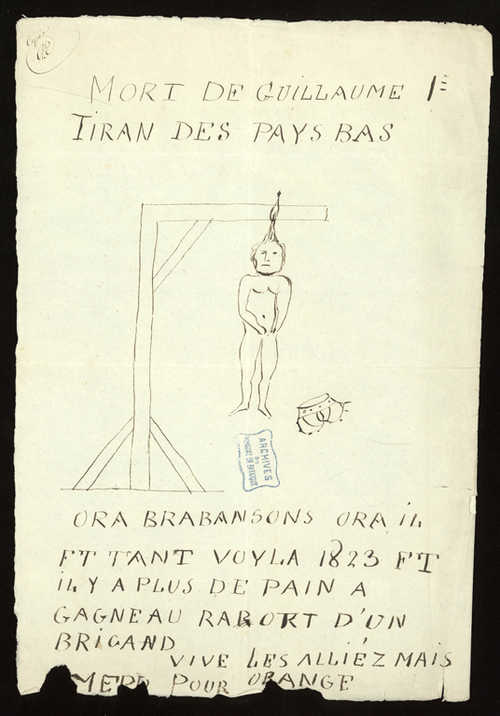

Despite his economic endeavours, the King is not popular among his southern residents. The Belgian liberals regard him as a ruler who is striving for absolute power and who is not prepared to give the educated elite a greater say. The Belgian Catholics object to the interference of the Protestant King in the training of novice priests. In their opinion, his religious involvement goes too far. The newspapers are increasingly deprived of their journalistic freedom. Furthermore, William demands that Dutch is spoken across much of the country, whereas the Belgian elite mainly speak French.

In 1830, the residents of Brussels revolt. “Death to William I, tyrant of the Netherlands”, the Belgian rebels write. William sends an army against them, but to no avail. Belgium regains its independence. Nevertheless, William keeps the army up for another nine years. The high costs that this entails damage the King’s popularity in the Netherlands. In 1839, William finally acknowledges Belgian independence. Disillusioned, he abdicates a year later, in favour of his son William II.