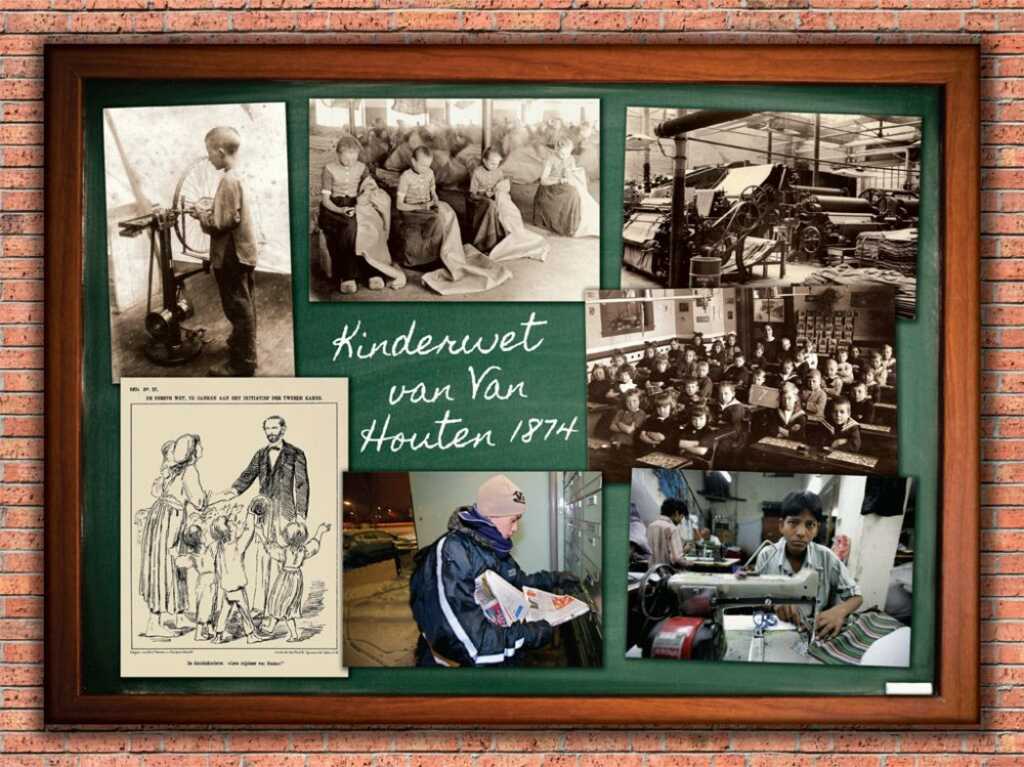

Child labour

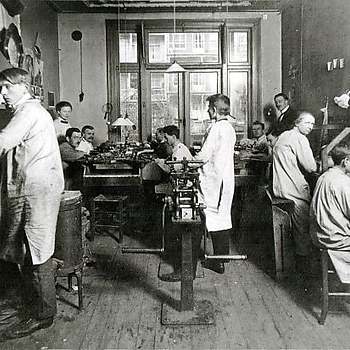

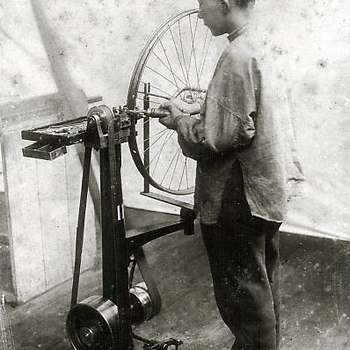

Throughout history, child labour has been a common phenomenon. Children work the fields, in shops or in workshops. This is not just regarded as useful – enabling them to learn a trade – but in many cases, it is a dire necessity to supplement the family income. During the Industrial Revolution, increasingly more children are put to work in factories, frequently under poor working conditions. A well-known case in point is the Petrus Regout glass factory in Maastricht, whose kilns burn day and night. The factory operates with two shifts, each working twelve hours at a stretch. Around midnight, children aged between eight and ten years old walk the streets half asleep to start their shift.

Criticism

From the early nineteenth century, legislation is introduced that somewhat curtails child labour. In 1839, such an Act is adopted in the German state of Prussia. Around 1860, child labour is increasingly criticised in the Netherlands. Physicians and teachers explain that the work performed by children jeopardises their health, and that children belong at school. Factory owners gradually come to realise that it would make more sense for them to hire children who have completed primary school. After all, children aged twelve and older, who can read and write, can be put to work in a wider range of factory jobs.

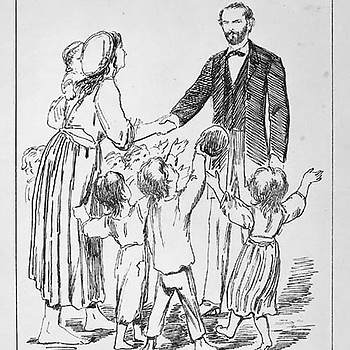

An important voice in the debate is that of author Jacob Jan Cremer. In 1863, after visiting a cloth factory in Leiden, he makes a burning plea to a select group of people gathered in The Hague. He sketches the horrible conditions under which children are forced to work and urges the King to abolish child labour with immediate effect. Among the shocked audience are several MPs and factory owners. Cremer’s plea comes as a bombshell and it is published under the title of Factory Children. That same year, under the pressure of public opinion, Minister Thorbecke establishes a state committee to investigate child labour.

Legislation

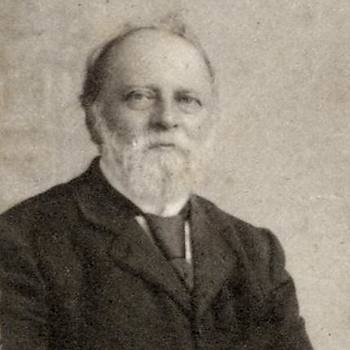

In 1874, liberal politician Samuel van Houten submits a private member’s bill against “excessive labour and neglect of children”. This bill prohibits children up to the age of twelve from working in workshops and factories. Although Van Houten pursues a general ban, the House of Representatives mitigates his bill. For example, children are still allowed to do farm work. And a lack of supervisory bodies precludes the abolition of child labour in factories with immediate effect. The 1901 Compulsory Education Act ends child labour once and for all. From that time onwards, parents are obliged to send their children between the ages of six up to and including twelve to school. In actual practice, most parents already do so. Around 1900, 90 per cent of children attend school.

Under the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), child labour is currently prohibited if it is “unhealthy or harmful”. Yet in 2019, as many as 152 million children across the globe are working, of whom 73 million under hazardous circumstances.