Independence

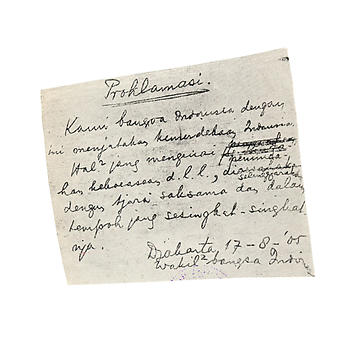

‘Proklamasi. Kami bangsa Indonesia dengan ini menjatakan kemerdekaan Indonesia…’

‘We, the people of Indonesia, hereby declare that Indonesia is independent …’

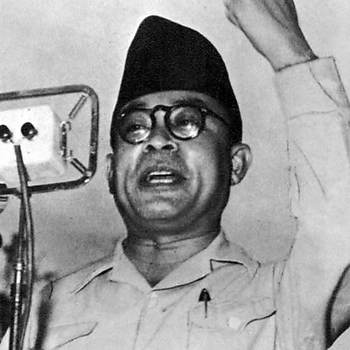

This is how Sukarno informed the world, in Jakarta on 17 August 1945, that the colonial Dutch East Indies definitively belonged to the past. Two days earlier, Japan had surrendered, following the atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This marked the end of World War II in Asia.

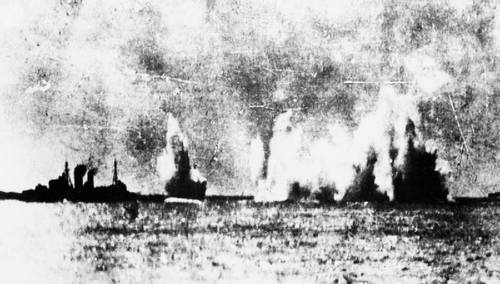

Even before the war, the Dutch East Indies harboured a comprehensive activist movement that advocated the right to self-determination. Leaders such as Sukarno, Mohammad Hatta, and Sutan Sjahrir pursue full independence, whilst others aim for increased autonomy. However, the Dutch authorities remain firmly in control. And then, in 1942, Japan invades the Dutch East Indies. On 27 February, the allied forces lose the Battle of the Java Sea and capitulation follows on 8 March. Soldiers are made prisoners of war and held captive under terrible circumstances. Dutch residents and later on, also Dutch residents of Indonesian descent, are detained in horrible camps. The administrative system of the Dutch East Indies is rendered inoperative by the Japanese and in effect, the Dutch East Indies cease to exist.

War of Independence

The Netherlands does not acknowledge the Republic of Indonesia. From 1945 onwards, it resorts to negotiations, warfare, and violence in an attempt to restore its rule, or at least stay in control of the decolonisation process. More than 200,000 troops partake in this war, over half of whom are conscripts. The largest military operations of the Netherlands are Operation Product in 1947 and Operation Crow in 1948-1949. During the latter, Sukarno is imprisoned. The two operations are referred to as “police actions”. The United Nations orders the Dutch to cease the military actions and to release the prisoners. The Netherlands does not cave in to the international pressure until May 1949. On the Indonesian side, more than 100,000 are killed during the period 1945-1949, versus some 5,000 on the Dutch side. On 27 December 1949, the transfer of sovereignty is signed in Amsterdam.

New Guinea is the only territory that is not relinquished until 1962. After a transitional period under UN supervision, the region is transferred to Indonesia in 1963, without taking account of the wishes of the Papua population. The state borders of the current Republic of Indonesia thus coincide with those of the former Dutch East Indies.

Migration

On account of the new balance of power, a total of more than 300,000 Dutch nationals, Dutch residents of Indonesian descent, and members of Indonesian minority groups (Moluccans, Papuans, Chinese) leave the country well into the 1960s. Most of them head for the Netherlands, among whom are 12,500 Moluccan soldiers of the former Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) and their families. They are promised a free Moluccan state to which they can return. However, this promise is never redeemed. In the 1970s, this results in shocking hijackings by young Moluccan activists.

Not a thing of the past

For a long period of time, the lost colonial war is hushed up. The views of the large group of veterans and a diverse group of migrants from the former colony differ widely. In 2008, the recognition of the war crimes is taken to court. A well-known example is the Rawagede case. In 1947, 431 men in the village of Rawagede in West Java were shot by Dutch troops. Some sixty years later, their widows sued the Dutch state for damages. In 2011, the court ruled that the widows are entitled to such compensation.

The Netherlands still struggles with the recognition of Sukarno’s proclamation and the subsequent war. In 2020, 75 years after the Proklamasi, King Willem-Alexander apologises for “excessive violence” during the war and congratulates Indonesia on 75 years of independence.