Trade union

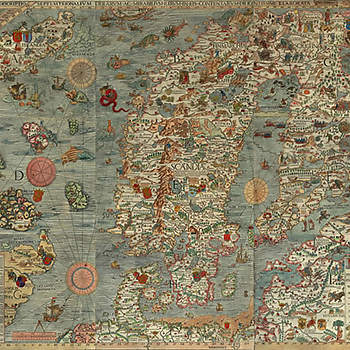

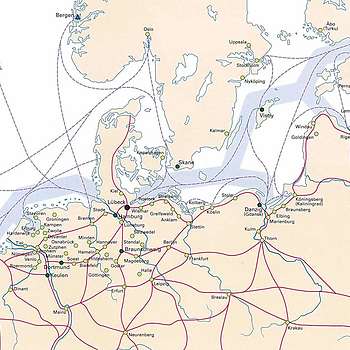

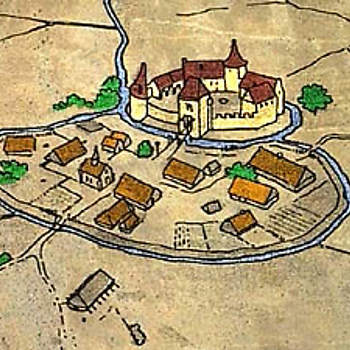

Between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, a number of Dutch cities, most of them situated in the eastern part of the country, develop into important and prospering trade centres. They owe their position to their membership of the Hanseatic League. Originally, the Hansa is an alliance between merchants from different cities trading in the same products. Collaboration enables them to cut their costs, travel collectively and therefore more safely, procure or sell on a wider scale, and collectively oppose decisions made by powerful rulers.

In 1356 a meeting is held in Lübeck, a town in what is now modern-day Germany. At this meeting it is decided that the Hanseatic League must become an association of cities, promoting urban interests, rather than a mere confederation of merchants. The Hanseatic League evolves into a powerful network of trading centres in the area bordering on the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. Within this network, the League attempts to solve trade issues wherever it can. The Hanseatic network also trades with partners outside its territory, for example, with London and with Spanish cities.

Expansion and boom

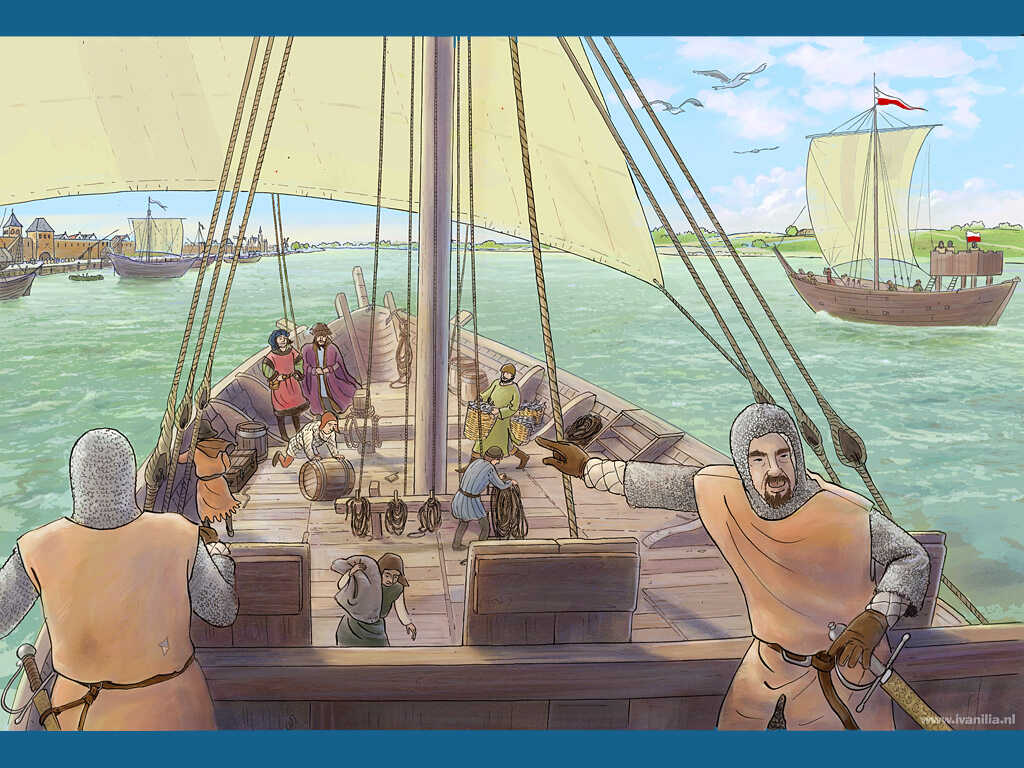

The trade in products such as salt, grains, fish, wood, wine, beer, animal skins, and cloth flourishes. The goods are largely transported by sea and by rivers, using cog ships of between fifteen to thirty metres in length. The cities blossom, reinforce their city walls, expand their ports, and become dotted with merchant homes, warehouses, and offices. The riches of the Hanseatic League are still clearly manifest in the aforementioned cities along the River IJssel, but also in smaller Hanseatic cities such as Stavoren, Hasselt, Tiel, and Doesburg.

Confidence

The Hanseatic cities gain confidence. In order to promote trade over land, in 1448 the Kampen city administration commissions the construction of a bridge across the River IJssel, without requesting permission from the bishop, the local sovereign. The new bridge is built within five months. The toll that each passing ship is required to pay flows into the city coffers.

Deventer and other Hanseatic towns around the Rivers IJssel and Rhine protest against this measure. They want free passage along the River IJssel and even complain to the bishop’s superior: Emperor Frederick III of the German Empire. He sends the city a letter ordering the demolition of the bridge. However, Kampen refuses to oblige. The Emperor and the bishop do not pursue the matter any further and the bridge stays put.

Mother of all trade

Trade to the Baltic Sea is also vitally important for non-Hanseatic cities such as Amsterdam. This trade forms the basis for the economic boom. Amsterdam is mainly trading in bulk goods such as grain and wood but has to compete with the IJssel cities. During the sixteenth century the power of the Hanseatic League declines. Holland is gaining economic strength at the expense of the IJssel cities that are hampered by a silting river. Only after the fall of Antwerp, in 1585, does Amsterdam become a truly important trade centre. Dutch trade becomes increasingly focused on the world seas. However, the trade to the Baltic Sea remains of such paramount importance to the Dutch economy and its food supply that it is referred to as the “mother of all trade”.